Blogpost

#Winning with MapServer, PostGIS and Ruby on Rails

This post was written for a game development project. We were building a real-time strategic running game. TL;DR: We used MapServer, MapCache, PostGIS, PostgreSQL, Open Street...

This post was written for a game development project. We were building a real-time strategic running game.

TL;DR: We used MapServer, MapCache, PostGIS, PostgreSQL, Open Street Map and a bunch of other awesome technologies to build fast and cheap maps for Jog of War. Here is how.

When we started building a custom maps solution for Jog of War, we had no idea how involved the setup would get or how many technology dependencies we would end up introducing. There were times mid-development where we were ready to give up on maps and pivot Jog of War towards something that would work without them. I am glad we didn’t, because the end result is awesome.

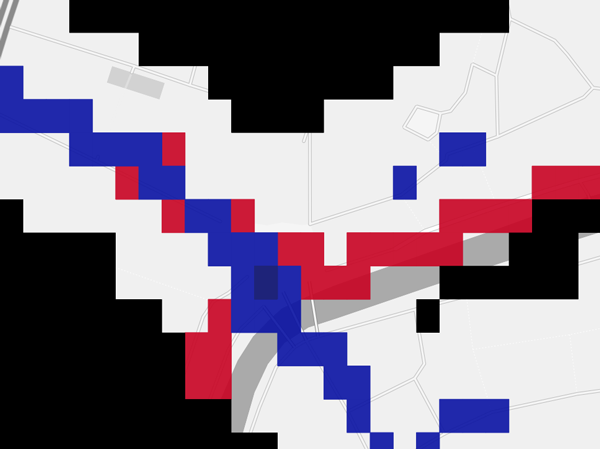

Me battling another player at the Preseren square in Ljubljana

Since there's so much potential in products based on—or aided by—an adaptable mapping setup, I can’t think of a better topic to cover in the last pre-beta blog post.

The requirements for Jog of War are simple in theory - we need a static base map, overlaid by a dynamic map showing the game state. And we need this setup to be cheap (free if possible), performant, scalable and pretty at the same time.

Base map

Starting with the base map, there’s quite a few options out there. At the very free (with some limitations) end of the spectrum, there’s Google Maps, which can play the role of a totally non-customisable base map. We wanted our maps to fit the general design of Jog of War and also to not interfere with game play, where we use colours to determine who owns a square and also whether a square is defended or not, so the colourful Google Maps were out. At the very not free end of the spectrum, there’s maps as a service offerings (MaaS), such as MapBox, which charges a minimum of 49 USD a month for non-branded maps, with a limit of a 100.000 map views. Calculated to Jog of War terms, that’s 10.000 users looking at 15 map tiles (which MapBox defines as 1 map view) every three days. We thought that was a bit expensive for what is essentially serving cached static images. Being out of obvious options, we decided to create our own map server.

So how do you actually serve your own maps? MapServer! MapServer is an open source map ... server. It has so many features and has such awesome documentation, that you can literally spend weeks if not months playing with it. But being on a tight schedule, we needed to get to the point quickly. The question at this stage was: Can MapServer render a detailed world map?

Let me pause here for a moment and say that the web mapping world is extremely confusing for someone out of the loop and it took a lot of time (days) to read up on enough things to have a basic understanding. What is SRID, what's a spherical projection, why can't I use planet.osm files in MapServer directly, what are slippy map tiles, how do you get a map displayed in a browser, what's a WMS? It seemed like this was way too much overhead for what is essentially a simple task, but in fact, rendering your own maps of the whole freaking world is incredibly simple these days compared to state of the art just a few decades ago, so in retrospect we can’t really complain. Considering the many unknowns, this was one of those moments where we wanted to abandon maps for a conceptually simpler alternative though, but if you’re at this stage you won’t regret sticking with it for a few more hours.

In our case, after wrapping our heads around some of these concepts and a few extremely exciting, if bland looking, attempts, we ended up just listening to MapServer’s own wiki, which guides you through the process of getting custom styled maps of our lovely planet (a 26 GB map provided by the awesome Open Street Map people) and came up with this style:

You can find our adapted basemaps style generator on GitHub.

I don’t know about you, but to me this is a very beautiful map. So yes, we were excited and happy, finally we had a base map worthy of its name!

We added a MapCache layer on top of this (PostgreSQL + PostGIS + MapServer), so that every time someone would request an already rendered tile MapServer wouldn't have to go to the database and render the tile again (very slow), but would simply read that tile from disk (very fast). It helps that MapCache and MapServer are made by the same people and they work together flawlessly.

As a side point, it takes a full day to process a planet.osm file into PostgreSQL database on a very very beefy machine and if you select the wrong projection the first time around ... it can be a time consuming process, so plan accordingly.

At this point, you’re probably wondering how static base maps and MapServer fit together with a dynamic datastore like PostgreSQL/PostGIS and I really can’t blame you. Introducing all these technologies into the dependency chain would be crazy if their only purpose was to serve static maps. It just so happens to be that these same tools are also very well suited for dynamic map rendering, which brings us to the second piece of the puzzle.

Dynamic game state map

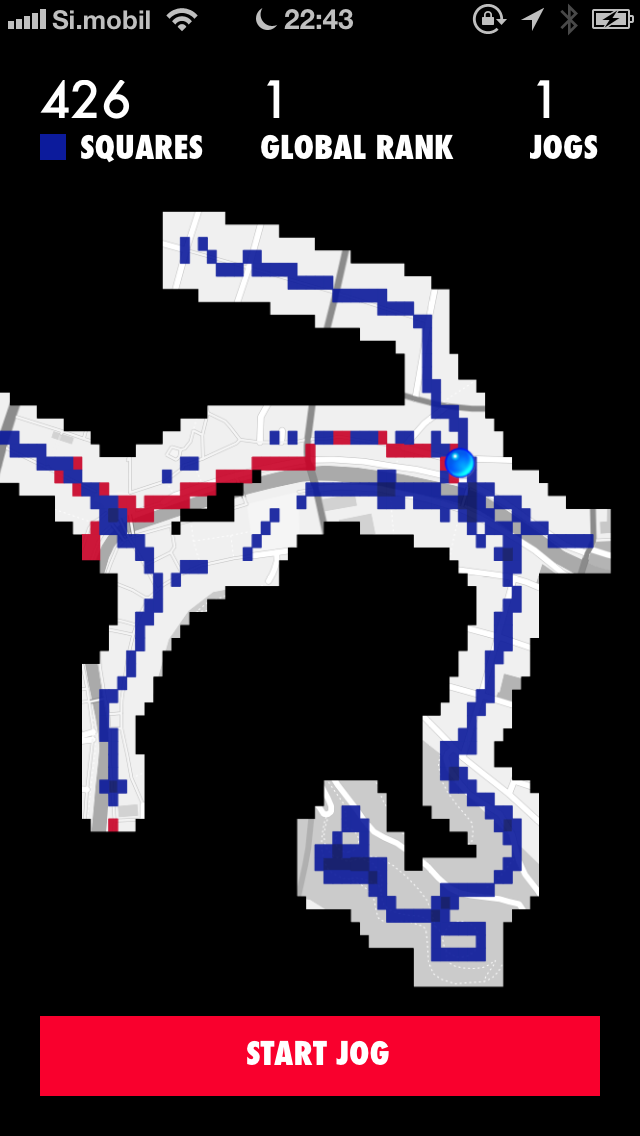

In Jog of War, you play turns (jogs) to lift the fog of war and conquer territory you are running over. Thus the end requirement for our maps was that they display a live view of both the fog, which is unique to each player, and the current ground situation (unconquered and conquered territory) which is a state shared by all players. Contrary to the base map, these factors are very dynamic and as such not cacheable, so we're heavily leaning on PostgreSQL and MapServer to be fast enough. Luckily we represent our game state with simple squares, which are fast to query from the database and fast to render, completely unlike the complex Open Street Map.

Our game logic is coded in Ruby, our web-backend built with Ruby on Rails and our API built with Grape. Yay, Ruby! But! If we want MapServer to render game state based on game logic situated in Ruby, we need to connect these two together somehow and since we're already using PostgreSQL as our regular SQL storage and our MapServer can already read and draw SQL data, PostGIS is the ideal candidate for this connection. Because of the amazing work of Daniel Azuma and the activerecord-postgis-adapter gem, connecting Ruby with PostGIS is refreshingly simple. Once you’re writing polygons to the database, drawing that in MapServer is as simple as adding a layer (shape is a column where geometry is stored and color is the column where color in #FFFFFF format is stored) to the MapServer map file:

LAYER

METADATA

"wms_title" "squares"

END

TYPE polygon

DATA "shape from squares"

CONNECTION "user=user password=password dbname=db host=localhost"

CONNECTIONTYPE postgis

NAME "Squares map"

STATUS ON

PROJECTION

"init=epsg:4326"

END

CLASS

STYLE

COLOR [color]

END

END

END

By using route-me, an open source map library, you should be able to get these maps to display in an iOS app fairly easily too, which completes the circle:

And that about wraps up this instalment of Jog of War development weekly. For those counting, we introduced a freakishly large number of dependencies. There’s the front-facing MapCache, MapServer, PostGIS supported by big projects like GEOS, Proj4 and GDAL ... and you probably didn’t even count server dependencies such as Lighttpd and Apache to run both MapServer and MapCache? But we do have a working setup we can always improve as the need arises. Most importantly, we met the requirements of the game and we’ve been having a lot of fun playing it with these beautiful maps providing the scenery.

This was a fairly long blog post but even so it’s likely that something obvious to me now (but definitely not then) was left out, so if you have any questions, let me know and I’ll be happy to help you out.